Midway Atoll's golden gooney chick, the first of its species hatched outside Japan, has fledged—flown out to sea, most likely to the rich waters to the northwest.

Midway Atoll's golden gooney chick, the first of its species hatched outside Japan, has fledged—flown out to sea, most likely to the rich waters to the northwest.

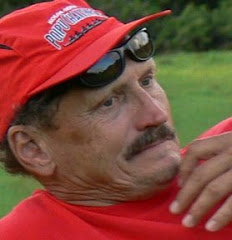

(Image: The golden gooney chick is still mostly black, but eventually will develop white plumage and a striking yellow-gold head, like its papa, shown here. The chick is seen here sitting under its dad. For more recent shots of the chick, check our previous posts (see links at the end of this story.) Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.)

“It happened just as most followers of the bird’s short life drama expected, the bird slipping away from the Atoll’s Eastern Island sometime during the day, with no one there to watch,” said a press release from John Klavitter of the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge.

Midway and the other Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, all part of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, are home to hundreds of thousands of Laysan albatross and black-footed albatross, but only within recent years have these cousins been joined by a handful of short-tailed albatross—also known as golden goonies for their yellow heads.

In January this year, a courtship between an 8-year-old male and 24-year-old female produced an egg that hatched into a healthy young bird. The chick has been knocked around some during its brief life, and was washed from its nest by the recent Japan tsunami.

In May it began stretching and flapping its wings, and in early June began paddling out to sea.

“The chick’s first swim in the ocean lasted 15 minutes. It walked into the lapping waters, paddled out 50 meters, submerged its head for a quick look, sipped some sea water, and then practiced flapping before paddling back to the shore. The chick was last seen the evening of June 15. By June 17 it was gone, most likely headed in a northwesterly direction to the rich and productive waters near Hokkaido, Japan, perhaps to join others of its kind,” a Fish and Wildlife Service release said.

Although its parents are both from Japanese-controlled islands, the birds normally return to their home islands to nest, and wildlife officials hope the chick will eventually settle on Midway for its own family.

“This event is a milestone in our international efforts to expand the range and population of this species,” said Fish and Wildlife Service Superintendent Tom Edgerton, one of seven co-stewards of the marine national monument.

“Once one of the world’s rarest birds, the endangered short-tailed albatross continues to recover,” said Refuge Manager Sue Schulmeister. “Sightings of the species have been relatively rare over the years, even on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. In the years to come, following this event, perhaps that will start to change.”

See earlier stories on the young golden gooney at RaisingIslands here, here, here and here.

© Jan TenBruggencate 2011